10/20/2021 – Comparative Method in Religion

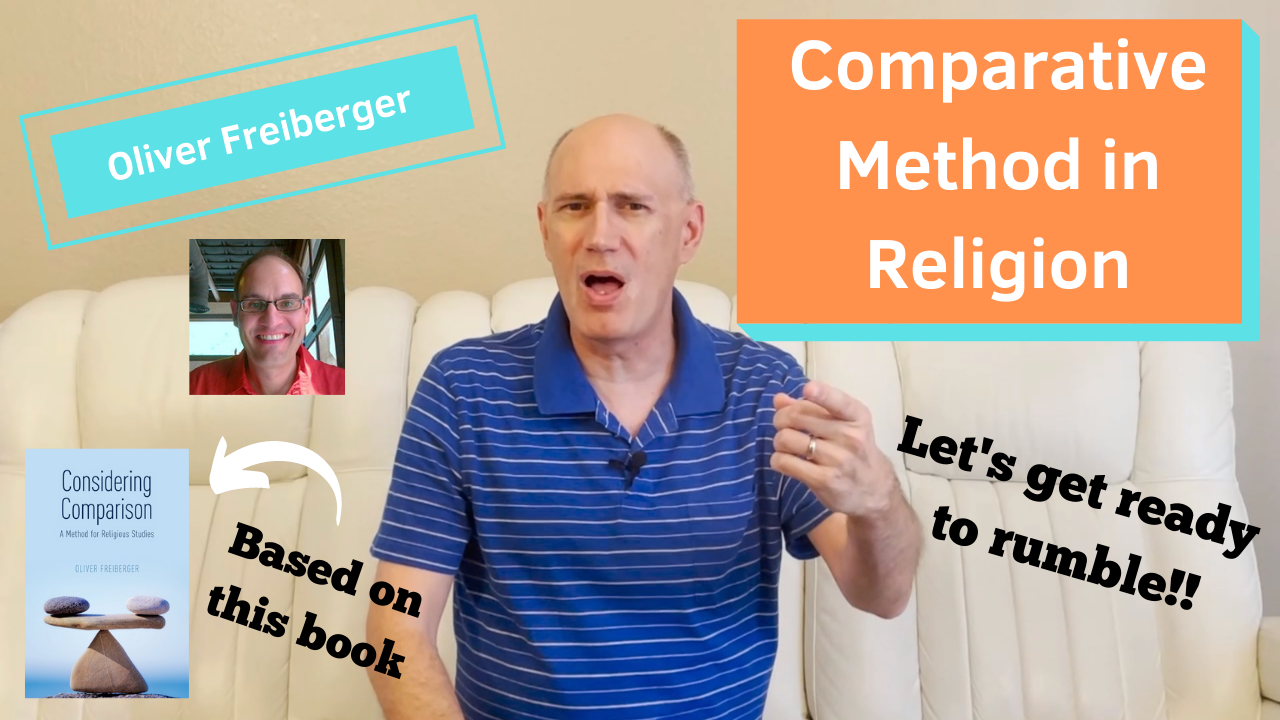

Welcome all you long-time listeners and those of you who are new to the channel. Today we’re going to talk about a book by Oliver Freiburger…Freeburger…what? He’s some kind of burger, hehehe… Was that inappropriate? I hope so. The book is Considering Comparison. Let’s get ready to rumbbleee… [Michael Buffer clip] I can’t really do it like Michael Buffer. Okay, anyways. This is TenOnReligion.

Hey peeps, it’s Dr. B. with TenOnReligion. This video is closed-captioned here on YouTube and the transcript is available at TenOnReligion.com. If you like religion and philosophy content one quick thing I need you to do is to smash that sub button because it really helps out the channel. I also have a ko-fi linked in the description if you’d like to help support the channel and help me keep this puppy going.

Oliver Freiberger, a scholar at the University of Texas, published Considering Comparison: A Method for Religious Studies in 2019 and I attended several sessions at the American Academy of Religion regarding his research contained in this book dating all the way back to 2015. By the way, he seems like a pretty nice guy. He says that the primary goal of religious studies is to better understand, and theorize about, religion. One important historical figure in the academic study of religion in the 1800’s was Max Müller who wrote about applying the comparative method, but since him, it has not been all that clear what the comparative method actually is. For example, a first order method of investigation is direct observation, and a second order method is the observation of other first order observations. Freiberger suggests that comparison is a second order method. It can be used in a positive way or in a negative or critical way, but not necessarily identified with either.

The problem with talking about comparison, however, evokes a philosophical problem that arose in the past century. One the one side, if something is taken too far out of its original context, distortion can occur. On the other side, if a broad pattern is imposed prior to any descriptive research, such as the attempt to find the “essence” of religion, distortion can also occur. So, the issue is, does comparison necessarily abstract and potentially misrepresent what is being compared? Are two things incomparable, as in always different with no possible connection to each other? Well, Freiberger cites William Paden who lists panhuman, universal behaviors shared by all cultures. This includes social behaviors such as forming bond and loyalties, sociocultural behaviors such as constructing histories and developing rituals, conceptual behaviors such as classifying the universe, and self-modification behaviors such as forming guiding and/or disciplining regimens. All of what I’ve mentioned so far is in the first two chapters of the book.

Chapters 3 and 4 represent the main part of the book’s content. Chapter 5 outlines the author’s former research as an example of the comparative method, which I’m not really going to get into today. So, we’re going to start with Chapter 3. It describes how one determines comparands, or what is it that one is comparing. Are they physical objects like statues, are they ideas or some other less empirical feature like concepts of religious purity? One is always limited in these choices based on one’s experiences up to that point in their life. This is similar to the philosophical concept of Gadamer’s horizon, which Freiberger doesn’t really mention but probably should have because it fits in well here. Maybe Gadamer’s horizon wasn’t a part of Freiberger’s horizon… (that was an inside joke for all you philosophers out there hehehe…sigh) but I digress. Freiberger writes that comparison is about investigating both similarities and differences. (Isn’t that technically contrasting not comparing?). He does offer an interesting point about the common apples and oranges idiom which usually means referring to two things which either should not or cannot be compared. But what we really mean when say “apples and oranges” is that two things should not be forced into a particular category. It’s not about the impossibility of comparison in any category, just the inappropriate assertion of sameness with respect to one particular category. Then he talks about what he refers to as the tertium comparationis, or the common factor that one will be utilizing in the comparison. Tertium means the point of view of which two items are being compared. He uses the idea of pre-comparative tertium, and foreknowledge, sort of like a hypothesis whether or not a certain category will work the way we expect it will work. Again, for you philosophers, this seems a lot like Heidegger’s hermeneutical circle of understanding. The situation of the comparativist – the person researching the comparison – includes personal factors, cultural factors, and academic factors such as education or alignment within a particular school of thought which greatly affects the entire process. Even though one obviously cannot avoid this, the goal is reflexivity, or active reflection on factors that might impact the scholarship. The identification of a category to be used in the comparison must also be modifiable or be able to be refined because as one goes through the process of researching, things might have to be tweaked a little bit here and there for everything to work and make sense.

Chapter 4 gets into describing the details of both the configuration and the process. The configuration is determined by mode, scale, and scope. The idea of modes goes back to the famous religious scholar Jonathan Z. Smith who delineated four of them: ethnographic, encyclopedic, morphological, and evolutionary. Freiberger makes some comments about them followed by a series of questions. He then goes on to mention a few other scholars and then ends up with two modes that he finds the most promising for comparative study: the illuminative mode and the taxonomic mode. The illuminative mode is illuminating a particular historical datum. When this is done in both directions this is called reciprocal illumination which Arvind Sharma wrote a book about explaining a lot of the different ways this can be done. The taxonomic mode classifies religious items, but the created categories employed to classify are constructed, and thus can be construed as abstractions, which can be further debated as to their usefulness and applicability. Freiberger lists three types of scale: micro, meso, and macro comparison. Macro comparison is like a large territory on a small map. Trying to get the big picture. Micro comparison compares items in a narrowly defined spatial or temporal situation. Trying to dig a well. Meso comparison is more in between the two, and thus a little more fluid in trying to determine the proper focus. Kind of like trying to take a panoramic photo of a landscape. Do I need to pan out a little bit more, or focus in a little more so the boundaries of the photo are what I want them to be? That’s meso comparison. The last part of the configuration, scope, can be contextual, cross-cultural, or trans-historical. Contextual means focusing more or less on a single historical or cultural context. Cross-cultural means moving beyond such boundaries. Trans-historical means using one of the first two scopes and then in addition moving across time as well. It’s not only a historical or cultural shift, but also a time shift. So, to configure a comparative investigation we have mode, scale, and scope.

After the configuration is determined, the comparative process itself consists of five overlapping and possibly repeating operations. First, selection, which is limited by feasibility and practicability and is often further refined throughout the process of research. Second, description and analysis, which is initially done with each of the comparands with respect to the category of comparison. Third, juxtaposition, where the similarities and differences of each comparand is identified with regard to the category and put side by side. Fourth, redescription, where one must redescribe some aspect of the results due to discovery of any blind spots in the comparison. This step doesn’t always happen, but one must be open to it. And fifth, rectification and theory formation, which is revision of the definition and conceptualization of the meta-linguistic categories involved in the study. Basically, formulating a meaningful result from the juxtaposition of these two or more comparands with this particular category. What can we learn from it? The last chapter, chapter 5, then provides a case study of his personal research in comparing ascetic discourses in historical texts in both Hinduism and Christianity, which I’m not going to talk about here, but if you’re interested, just look up his research on the topic.

So, what do I think about all this? On the positive side Freiberger does a great job at explaining the various factors that affect the comparative endeavor as well as providing some good details at creating a comparative project in religious studies. On the negative side, hermeneutical theory affects this entire process from start to finish and there are some very obvious figures left out of this book which could have greatly enhanced the overall presentation. I already mentioned two of them, Heidegger and Gadamer, and also Paul Ricoeur. All three of these figures along with many others, have a lot to offer about interpretation and understanding which could be applied to the comparative process. One final criticism where he dismisses comparative theology as strictly a Christian activity is a misrepresentation of comparative theology. Comparative theology is how we can understand religions different from our own, regardless of one’s starting point, which doesn’t seem too different from what Freiberger is attempting to do here. He posits himself as being objective and distanced since he works at a public institution, but there are limitations to that approach. We are all existential in living our lives and this includes scholarly research in religion and not fully embracing that and incorporating it seems a little disingenuous. But maybe I’m being a little too harsh here. Not sure about that.

So, what do you think about Freiberger’s attempt at explaining the comparative method in religion? Leave a comment and let me know what you think. Until next time, stay curious. If you enjoyed this, support the channel in the link below, please like and share this video and subscribe to this channel. This is TenOnReligion.