04/26/2023 – What Is Interrituality?

Have you ever thought about participating in another religion’s rituals? What would that be like? How would you feel about being in a different sacred space? Or if the roles were reversed, how would you feel about hosting someone from another religion to visit and participate in your tradition? These are some interesting questions, to say the least. There’s a lot going here in this episode. Check this out. This is TenOnReligion.

Hey peeps, it’s Dr. B. with TenOnReligion. If you like religion and philosophy content one thing I really need you to do is to smash that sub button because it really helps out the channel. The transcript is available at TenOnReligion.com and new episodes are posted about every two weeks, at noon, U.S. Pacific time, so drop me some views.

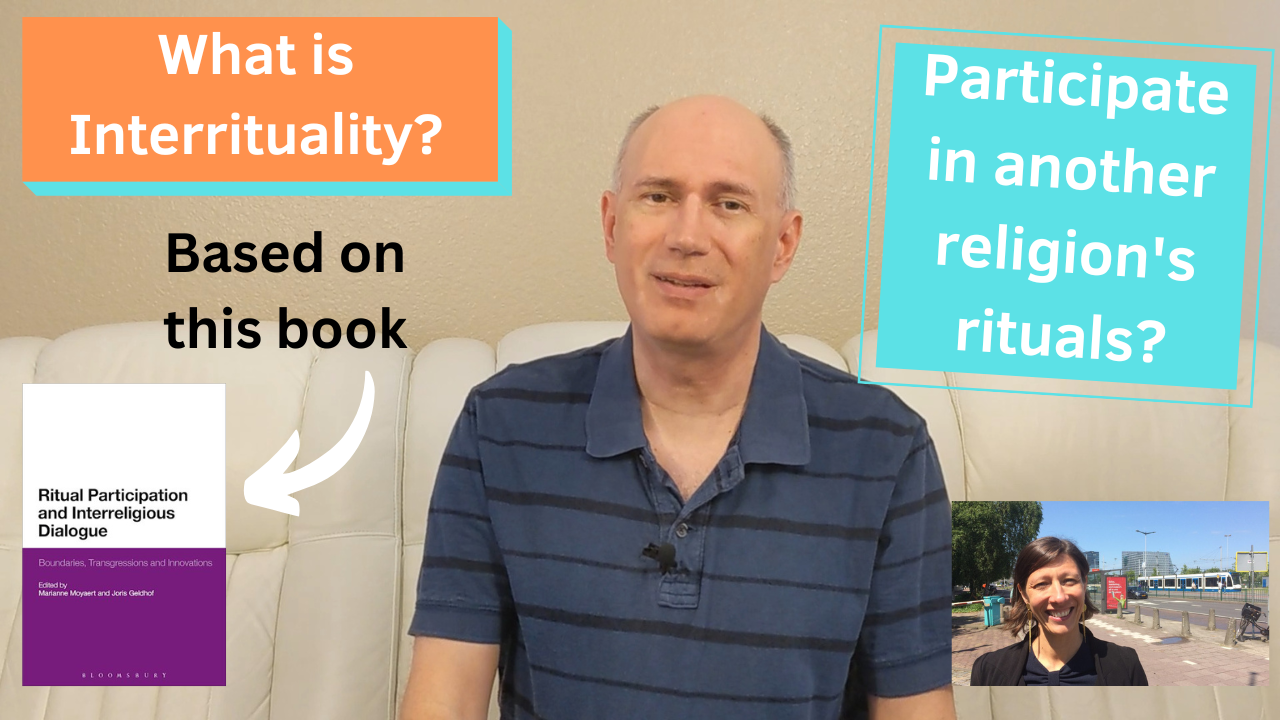

In the last episode I mentioned that when I went to the American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting in Denver in November 2022, I met a European religion scholar I’ve wanted to meet for a long time named Marianne Moyaert. We had a short chat and I mentioned I’d like to do an episode or two about some of her views on this channel and here we are. The last episode was on interreligious hospitality and this episode is going to be on interrituality based on book she edited with Joris Geldhof titled, Ritual Participation and Interreligious Dialogue. I’m sure you have a lot of questions about this as I did, so let’s get into it.

Let’s just start off by addressing the elephant in the room. What in the world is interrituality? Basically, as more and more people experience religious diversity firsthand and are touched by the vividness of other religious traditions and by the spiritual and moral wisdom of the "other," they also increasingly ask if they can celebrate religiously with believers belonging to other religious traditions. The religious journey from monologue to dialogue seems to be continued in the sphere of rituality. Moyaert explains there are two main types of ritual participating: one, responsive and outer-facing; and two, extending or receiving hospitality and inner-facing. Outer-facing ritual participation is in response to an external event such as war, a national calamity or natural disaster, or something like systemic discrimination or racism. This response creates a “we” in the face of some shared challenge. Inner-facing ritual participation means extending hospitality to strangers to visit one’s place of worship to celebrate or even participate in the ritual life of one’s own religious community. One must prepare to receive guests in one’s house of worship or home and allow the guests to participate to some degree. Now already you sense a difficulty with this, and herein lies one of the challenges in this scenario: how to find the right balance between loyalty to one’s own tradition and openness to the other. Now I’m not saying this is easy by any stretch of the imagination, but if the right balance can be found, Moyaert suggests that ritual hospitality may penetrate deeper than any other form of interreligious dialogue. It holds the promise and possibility of accessing the lifeblood, the beating heart of another religion, and touch the participants on a deeply emotional level. Let’s try to unpack what this might mean a little bit more.

If you’re watching or listening to this from a Western country, this might sound quite strange. But in other parts of the world the idea that one should restrict oneself to one tradition’s rituals makes little sense. What is at stake is not “confessionality” but rather efficacy – does the ritual work? But in the West “to belong” almost always implies “to believe.” If religious truths and religious rituals are so intertwined this means that rituals should only be performed by those who believe, which obviously limits the possibilities of sharing in ritual participation. If one doesn’t share the religious convictions, than participating in those rituals can be seen as being disrespectful or inauthentic. But what exactly is a ritual? Ritual means doing something like making the sign of the cross, lighting candles, participating in a Passover meal, body postures during prayer or meditation, chanting or singing, and so much more, but you get the picture. Since the human body is so essential to all these activities, there is potentially transformative power involved. This may be one reason why people feel wrong to enter into another’s sacred space and ritually “cross over” to another religion, even if temporarily. This is why so many feel like participating in the rituals of another tradition is a rather risky business. But does it have to be that way?

Ritual is about conforming to a set pattern. It tends to resist creativity and innovation because it is focused on the right performance, namely, doing things the right way they should be done according to the tradition. Participating in an authentic way means being part of a greater narrative than oneself and this binds people together into a community with a shared memory for the past and a shared destiny for the future. In this sense, rituals become sort of like boundary markers between “us” (the insiders) and “them” (the outsiders). Now here’s where things get interesting. What happens when monoreligious worship is challenged? In the past century or so, scholars have noticed a change in human thinking called the subjective turn. The subject is called to exercise authority in the face of great existential questions including exploring beyond traditional religious boundaries. In this framework, ritual participation can be understood as an expression of an ongoing spiritual journey which does not necessarily allow itself to be fixed in rigid, bounded traditions. If one acknowledges that these bounded traditions are really arbitrary constructs over time, as in historically or culturally determined creations, it then becomes more and more difficult to justify traditional authoritative claims to being an exclusive religious community based on rituals. Why not break through ritual boundaries and enrich one’s religious perspective by means of inter-ritual sharing?

Now that was the gist of Marianne’s introductory chapter explaining the idea of interrituality. There were so many chapters in this book, I can’t even come close to talking about them all, but I do want to highlight a few things. First, Martha Moore-Keish’s chapter mentions five insights on interreligious ritual participation. I found them very interesting. First, ritual action, not only doctrinal teaching, shapes faith. Second, different religious rituals have different thresholds of participation. Third, participants often approach the same ritual with different interpretive frameworks. Fourth, religious communities are not clearly separated from one another and this kind of blurs the boundaries implied in the question of engaging in someone else's ritual. Last, ritual participation is a complex term, and often the question is not whether one can participate in the rituals of others, but how. That last point seems really important and when two or more religions try to work together to create some sort of unified event, there’s a lot of discussion and negotiation on the “how” part of the equation.

I also want to mention something from Rachel Reedijk’s chapter on ritual boundaries. She indicated that in some cases ritual participation may enhance exclusion because guests and visitors are transformed into obvious outsiders. Outsiders may experience awkwardness, embarrassment, resentment, or shame. They clearly do not all stand on common ground. I taught a college-level world religions course for fourteen years and each semester had students visit local religious places of worship for observational purposes and write about their experience. The far majority of students had a positive encounter and thoroughly enjoyed the assignment. But there were a few situations in which the student did not feel entirely welcomed and did not really know how to properly negotiate that social situation. They did feel awkward, so that certainly exists as a possible outcome.

Whereas Marianne Moyaert wrote a hearty introduction, the other editor of the book, Joris Geldhof, wrote a short epilogue about four categories he felt were thematically important throughout the various chapters. The last one he mentioned was sensitivity and I can thoroughly understand this to be crucial. This reminds of the last episode on interreligious hospitality. Whether one plays the role of religious host or religious guest, it just seems like it to me that the higher degree of sensitivity on both parties, the more likely a positive experience will occur. Sensitivity is definitely a key component of the entire process.

So, what do you think about interrituality? Is interreligious ritual participation something that can be seen as potentially beneficial in understanding and bridging the divide between religious communities? Leave a comment below and let me know what you think. I hope you’ve appreciated this two-part series on Marianne Moyaert. Until next time, stay curious. If you enjoyed this, support the channel in the link below, please like and share this video and subscribe to this channel. This is TenOnReligion.

Ritual Participation and Interreligious Dialogue: Boundaries, Transgressions and Innovations, edited by Marianne Moyaert and Joris Geldhof(London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2015).